Types of Castle & The History of CastlesAncient Castles & Roman Forts |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Ancient Castles

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

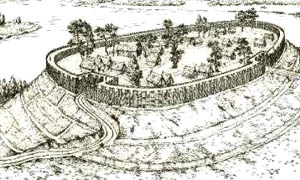

Early European Fortifications

It was not until the Bronze Age that hill forts were developed in Europe, which then proliferated across Europe in the Iron Age. These structures used earthworks rather than stone as a building material. Many earthworks survive today, along with evidence of palisades to accompany the ditches. In Europe, opida emerged in the 2nd century BC; these were densely inhabited fortified settlements, such as the opidum of Manching, and developed from hill forts. The Romans encountered fortified settlements such as hill forts and opida when expanding their territory into northern Europe. Although primitive, they were often effective, and were only overcome by the use of siege engines and other siege warfare techniques. The Romans' own fortifications (castra) varied from simple temporary earthworks thrown up by armies on the move, to elaborate permanent stone constructions. Maiden Castle is an Iron Age hill fort 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) south west of Dorchester, in the English county of Dorset.] Hill forts were fortified hill-top settlements constructed across Britain during the Iron Age. The name Maiden Castle may be a modern construction meaning that the hill fort looks impregnable, or it could derive from the British Celtic mai-dun, meaning a "great hill." |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Oppida

An oppidum (plural oppida) is a large defended settlement., the earliest ones dat back to the Iron age. Oppida are associated with the Celtic La Tène culture, emerging during the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, spread across Europe, stretching from Britain and Iberia in the west to the edge of the Hungarian plain in the east. They continued in use until the Romans began conquering Europe. North of the River Danube, where the population remained independent from Rome, oppida continued to be used into the Oppidum is a Latin word meaning the main settlement in any administrative area of ancient Rome. The word is derived from the earlier Latin ob-pedum, "enclosed space". Julius Caesar described the larger Celtic Iron Age settlements he encountered in Gaul as oppida, and the term is now used to describe the large pre-Roman towns that existed all across western and central Europe. The main features of the oppida are the walls and gates, the spacious layout, and commanding view of the surrounding area. Size and construction varied considerably. Typically oppida in Bohemia and Bavaria were larger than those found in the north and west of France. Typically oppida in Britain are small, but there is a group of large oppida in the south east; though oppida are uncommon in northern Britain, Stanwick stands out as an unusual example as it covers 350 hectares (860 acres). Stone walls supported by a bank of earth, called Kelheim ramparts, were characteristic of oppida in central Europe. To the east timbers were often used to support the earthen ramparts, called the Preist type. In western Europe, the murus gallicus, a timber frame nailed together, was the dominant form of rampart construction. Dump ramparts, that is earth unsupported by timber, were common in Britain and were later adopted in France. Oppida can be divided into two broad groups, those around the Mediterranean coast and those further inland. The latter group were larger, more varied, and spaced further apart. Oppida originated in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. Most were built on fresh sites, usually on an elevated position. Such a location would have allowed the settlement to dominate nearby trade routes and may also have been important as a symbol of control of the area. While some oppida grew from hill forts, by no means all of them had significant defensive functions. The development of oppida was a milestone in the urbanisation of the continent as they were the first large settlements north of the Mediterranean that could genuinely be described as towns. Caesar pointed out that each tribe of Gaul would have several oppida but that they were not all of equal importance, perhaps implying some form of settlement hierarchy. Oppida continued in use until the Romans began conquering Iron Age Europe. In Germany north of the River Danube, which remained unsubdued by the Romans, oppida continued in use until the late 1st century AD. In conquered lands, the Romans used the infrastructure of the oppida to administer the empire, and many became full Roman towns. This often involved a change of location from the hilltop into the plain. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Roman Forts

Roman forts were generally located in permanent military encampments called castra. In English, the terms Roman Fortress, Roman Fort and Roman Camp are generally used to denote these castra. In classical Latin the word castrum denotes a legionary encampment, whether temporary, semi permanent or permanent. A large encampment was a castrum, and a small one a castellum (from which we get the English word castle) The best known type of castrum is the Camp. This was a military town designed to house and protect the soldiers along with their equipment and supplies when they were not fighting or marching. More permanent camps were castra stativa, "standing camps". Less permanent castra were castra aestiva or aestivalia, "summer camps", in which the soldiers were housed in tents. Summer was the military campaign season. For the winter the soldiers retired to castra hiberna containing barracks of more solid materials, public buildings and stone walls. The Camp allowed the Romans to keep a rested and supplied army in the field. Neither the Celtic nor Germanic armies had this capability. They found it necessary to disperse after a few days. Even when assembled, their open camps invited attack. When legions were far from a permanent camp they needed to construct a temporary castrum. Regulations required a major unit in the field to retire to a properly constructed fort every day. To this end a marching column carried in a baggage train of wagons and on the backs of the soldiers, the equipment needed to build and stock the camp. Camps were the responsibility of engineering units with specialists of many types, officered by architects, "chief engineers", who requisitioned manual labour from the soldiers at large as required. An architect could throw up a camp in a few hours while under enemy attack. Judging from the names, they seem to have used a selection of standardised camp plans, selecting the one depending on the length of time a legion would spend in it: tertia castra, quarta castra, etc., "a camp of three days", "four days", etc. The standard was a linear plan for a camp or fort: a square for camps to contain one legion or smaller unit, a rectangle for two legions, each legion being placed back-to-back with headquarters next to each other. Laying it out was a geometric exercise conducted by officers called metatores. The process started in the centre of the planned camp at the site of the headquarters tent or building (principia). Streets and other features were marked with coloured pennants or rods. The base fortification (munimentum) was placed within a wall (vallum). The vallum was quadrangular aligned on the cardinal points of the compass. Construction crews dug a trench (fossa), throwing the excavated material inward, to be formed into the rampart (agger). On top of this a palisade of stakes (sudes or valli) was erected. Soldiers carried these stakes on the march. Over the course of time, the palisade might be replaced by a fine brick or stone wall, and the ditch serve also as a moat. A legion-sized camp always placed towers at intervals along the wall with positions between for the division artillery. This basic pattern was to endure long after the fall of the Roman Empire, being copied for centuries in generation after generation of castle. Around the inside periphery of the vallum was a clear space, the intervallum, which served as an access route to the vallum and as a storage space for cattle (capita) and booty (praeda). Legionaries were quartered in a peripheral zone inside the intervallum, which they could rapidly cross to take up position on the vallum. Inside of the legionary quarters was a peripheral service road (Via sagularis). Every camp included a very wide main street, which ran through the camp on a north-south axis. The names of streets in many cities formerly occupied by the Romans suggest that the street was called cardo or Cardus Maximus. Typically the main street was the via principalis. The central portion was used as a parade ground and headquarters area. The "headquarters" building was called the praetorium because it housed the base commander, praetor ("first officer"), and his staff. On one side of the praetorium was the quaestorium, the building of the supply officer, or quaestor ("seeker"). On the other side was the forum, a small duplicate of an urban forum, where public business could be conducted. Along the Via Principalis were the homes or tents of tribunes in front of the barracks of the units they commanded. At one end the Via Principalis passed through the vallum in the "right principal gate” (Porta principalis dextra ) and at the other in the "left principal gate (Porta principalis sinistra), which were gates fortified with towers (turres). (Which was on the north and which on the south depends on whether the praetorium faced east or west, which is one of the many details of Roman camps that remains unknown.) The central region of the Via Principalis with the buildings for the command staff was a square called the Principia. Across this at right angles to the Via Principalis was the Via Praetoria, so called because the praetorium interrupted it. The Via Principalis and the Via Praetoria divided the camp into four quarters. Across the central plaza (principia) to the east or west was the main gate, the Porta praetoria. Marching through it and down "headquarters street" a unit ended up in formation in front of the headquarters where the standards of the legion were displayed. On the other side of the praetorium the Via Praetoria continued to the wall,which it passed through the back gate (Porta Decumana). Supplies came in through it and so it was also called the Porta quaestoria. The street plan of various present-day cities still retains traces of a Roman camp, for example Marsala in Sicily. Due to local archaeology, the locations and layouts of Roman castra are rapidly becoming known. Both amateurs and professionals are involved in excavation and publication. Internet sites giving photographs and the texts of inscriptions are numerous. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Photographs |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

More on Types of Castle and History of Castles

Click on any of the following links to learn more about specific types of castle

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| :::: Link to us :::: Castle and Manor Houses Resources ::: © C&MH 2010-2014 ::: contact@castlesandmanorhouses.com ::: Advertising ::: |

.jpg)