Life In A Medieval CastleMedieval Clothing |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medieval Clothing

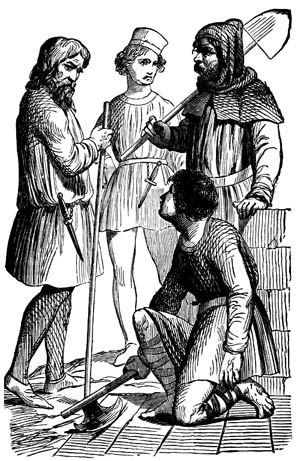

Most people in the Middle Ages wore woollen clothing, with undergarments (if any) made of linen. Among the peasantry, wool was generally shorn from the sheep and spun into the thread for the cloth by the women of the family. Dyes were common, so even the lower class peasants frequently wore colourful clothing. Using plants, roots, lichen, tree bark, nuts, crushed insects, molluscs and iron oxide, virtually every colour could be achieved. Dyes came from different sources, some of them more expensive than others. Even the humble peasant could have colourful clothing. Dyed fabric would fade if it was not mixed with a mordant. Bolder shades required either longer dyeing times or more expensive dyes. Fabrics of the brightest and richest colours cost more and were therefore most often found on nobility and the very rich. Brighter colours, better materials, and a longer jacket length were usually signs of greater wealth. Men wore stockings (hose) and tunics. Noblemen wore tunics or jackets with hose, leggings and breeches. The wealthy also wore furs and jewellery. Women wore long gowns with sleeveless tunics and wimples to cover their hair. Sheepskin cloaks and woollen hats and mittens were worn in winter for protection from the cold and rain. Women wore flowing gowns and elaborate headwear, ranging from headdresses shaped like hearts or butterflies to tall steeple caps and Italian turbans. Throughout much of the Middle Ages and in most societies, undergarments worn by both men and women didn't substantially change. They consisted of a shirt or undertunic, stockings or hose, and, for men at least, underpants. Illuminations, woodcuts, and other period artwork illustrate medieval people in bed in different attire; some are unclothed, but just as many are wearing simple gowns or shirts, some with sleeves. We have virtually no documentation regarding what people wore to bed, but from these images it is clear that that those who wore night dress would have been clad in an under-tunic, possibly the same one they had worn during the day. Leather boots were covered with wooden patens to keep the feet dry. Outer clothes were almost never laundered, but the linen underwear was regularly washed. The smell of wood smoke that permeated the clothing seemed to act as a deodorant. Clothing of the aristocracy and wealthy merchants tended to be elaborate and changed according to the dictates of fashion. Fur was often used to line the garments of the wealthy. Jewellery was lavish, much of it imported. Gem cutting had not been invented until the fifteenth century, so most stones were not lustrous. Ring brooches were the most popular item from the twelfth century on. Diamonds became popular in Europe in the fourteenth century. By the mid-fourteenth century there were laws to control who wore what jewellery. Knights were not permitted to wear rings. Sometimes clothes were garnished with silver, but only the wealthy could wear such items. Virtually everyone wore something on their heads in the Middle Ages, to keep off the sun in hot weather, to keep their heads warm in cold weather, and to keep dirt out of their hair. as with every other type of garment, hats could indicate a person's job or station in life and could make a fashion statement. Hats were especially important, and to knock someone's hat off his or her head was a grave insult that, depending on the circumstances, could even be considered assault. Types of men's hats included wide-brimmed straw hats, close-fitting coifs of linen or hemp that tied under the chin like a bonnet, and a wide variety of felt caps. Women wore veils and wimples; among the fashion-conscious nobility of the High Middle Ages, some fairly complex hats and head rolls were in vogue. Both men and women wore hoods, sometimes attached to capes or jackets but sometimes standing alone. Some of the more complicated men's hats were hoods with a long strip of fabric in the back that could be wound around the head. A common accoutrement for men of the working classes was a hood attached to a short cape that covered just the shoulders. Most of the holy orders wore long woollen habits in emulation of Roman clothing. . St. Benedict stated that a monk's clothes should be plain but comfortable and they were allowed to wear linen coifs to keep their heads warm. Benedictines wore black; the Cistercians, undyed wool or white. Franciscans wore grey, and later brown. Silk was the most luxurious fabric available to medieval Europeans, and it was so costly that only the upper classes, and churchmen, could afford it. While its beauty made it a highly-prized status symbol, silk has practical aspects that made it much sought-after. It is lightweight yet strong, resists soil, has excellent dyeing properties and is cool and comfortable in warmer weather. Western Europeans imported silks from Byzantium, but also import them from India and the Far East,. Wherever it came from, the fabric was so costly that its use was reserved for church ceremony and cathedral decorations. Muslims, who had conquered Persia and acquired the secret of silk, brought the knowledge to Sicily and Spain.From there, it spread to Italy. By the 13th century European silk was competing successfully with Byzantine products. For most of the Middle Ages, silk production spread no further in Europe, until factories were set up in France in the 15th century. Laws dating back to the Romans restricted ordinary people in their expenditure. These were called Sumptuary Laws. The word Sumptuary is derived from the Latin word for expenditure. English Sumptuary Laws were imposed to curb the expenditure of the people. Sumptuary laws might apply to food, beverages, furniture, jewellery and clothing. These Laws were used to control behaviour and ensure that a specific class structure was maintained. Penalties for violating Sumptuary Laws could be harsh - fines, the loss of property, title and even life. The first record of sumptuary legislation is an ordinance of the City of London in 1281 which regulated the apparel, or clothing, of workman. These related to workers who had working clothes supplied by their employer as a part of their wages. The second record of sumptuary legislation occurred during the reign of King Edward II (1284-1327) related to food expenditure. King Edward II issued a proclamation against 'outrageous consumption of meats and fine dishes' by nobles. The next records of sumptuary legislation occurred during the reign of King Edward III (1312-1377). King Edward III passed these Sumptuary Laws to regulate the dress of various classes of the English people, promote English garments and to preserve class distinctions by means of costume, clothes and dress. The sumptuary legislation of 1336 attempted to curb expenditure and preserve class distinction. One of acts stated the following:

The sumptuary legislation of 1337 was designed to promote English garments and restrict the wearing of furs. English Sumptuary legislation passed in 1363 included the following:

These Sumptuary Laws distinguished social categories and made members of each class easily distinguished by their clothing

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

More on Life in a Medieval Castle

Introduction to Life in a Medieval Castle

Officers & Servants in a Medieval Castle

Mills: Windmills and Water Mills

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| :::: Link to us :::: Castle and Manor Houses Resources ::: © C&MH 2010-2014 ::: contact@castlesandmanorhouses.com ::: Advertising ::: |