Types of Castle and The History of CastlesStar Forts |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Post-gunpowder castlesStar Forts

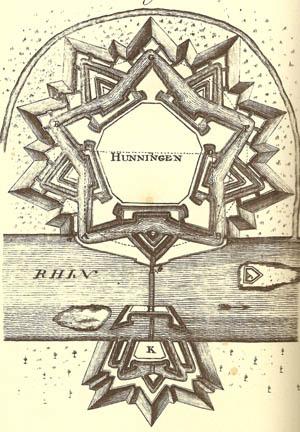

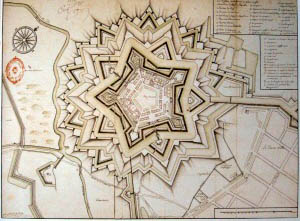

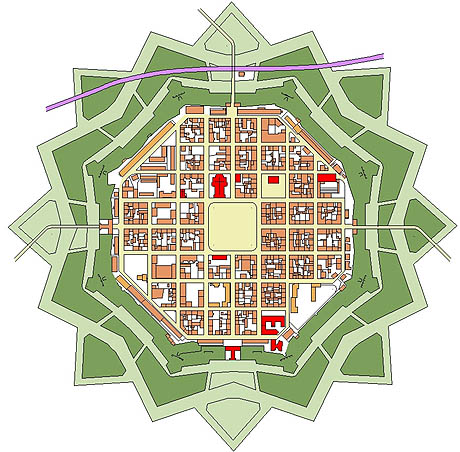

A star fort, or trace italienne, is a fortification in the style that evolved during the age of gunpowder when cannon came to dominate the battlefield. It was first seen in the mid-15th century in Italy. Passive ring-shaped (enceinte) fortifications of the Medieval era proved vulnerable to damage or destruction by cannon fire, when it could be directed from outside against a perpendicular masonry wall. In addition, an attacking force that could get close to the wall was able to conduct undermining operations in relative safety, as the defenders could not shoot at them from nearby walls. In contrast, the star fortress was a very flat structure composed of many triangular or lozenge shaped bastions designed to cover each other, and a (typically dry) ditch. Further structures, such as ravelins, hornworks or crownworks, and detached forts could be added to create a complex symmetrical structure. Star fortifications were further developed in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries primarily in response to the French invasion of the Italian peninsula. The French army was equipped with new cannon and bombards that were easily able to destroy traditional fortifications built in the Middle Ages. In order to counteract the power of the new weapons, defensive walls were made lower and thicker. They were built of many materials, usually earth and brick, as brick does not shatter on impact from a cannonball as stone does. Another important design modification were the bastions that characterized the new fortresses. In order to improve the defence of the fortress, covering fire had to be provided, often from multiple angles. The result was the development of star-shaped fortresses. The design was employed by Michelangelo in the defensive earthworks of Florence, and refined in the sixteenth century by Alcazar Peruzzi and Scamozzi. The design spread out of Italy in the 1530s and 1540s. It was employed heavily throughout Europe for the following three centuries. Italian engineers were heavily in demand throughout Europe to help build the new fortifications.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The late-seventeenth-century architect Menno van Coehoorn and Marshal de Vauban, Louis XIV's military engineer, are considered to have taken the form to its logical extreme. "Fortresses... acquired ravelins and redoubts, bonnettes and lunettes, tenailles and tenaillons, counterguards and crownworks and hornworks and curvettes and fausse brayes and scarps and cordons and banquettes and counterscarps..." The star-shaped fortification had a formative influence on the patterning of the Renaissance ideal city: "The Renaissance was hypnotized by one city type which for a century and a half—from Filarete to Scamozzi—was impressed upon all utopian schemes: this is the star-shaped city." In the nineteenth century, the development of the explosive shell changed the nature of defensive fortifications and star forts became obsolete. The predecessors of star fortifications were medieval fortresses, usually placed on high hills. From there, arrows were shot at the enemies, and the higher the fortress was, the further the arrows flew. The enemies' hope was to either ram the gate or climb over the wall with ladders and overrun the defenders. For the invading force, these fortifications proved difficult to overcome. When the newly effective manoeuvrable siege cannon came into military strategy in the fifteenth century, the response from military engineers was to arrange for walls to be embedded into ditches fronted by earth slopes so that they could not be attacked by direct fire and to have the walls topped by earth banks that absorbed and largely dissipated the energy of plunging fire. Where conditions allowed, as in Fort Manoel in Malta, ditches were cut into the native rock, and the wall at the inside of the ditch was simply unquarried native rock. As the walls became lower, they also became more vulnerable to assault. Worse still, the rounded shape that had previously been dominant for the design of turrets created "dead space", or "dead" zones which was relatively sheltered from defending fire, because direct fire from other parts of the walls could not be shot around the curved wall. To prevent this, what had previously been round or square turrets were extended into diamond-shaped points to give storming infantry no shelter. Ditches and walls channeled attacking troops into carefully constructed killing grounds where defensive cannons could wreak havoc on troops attempting to storm the walls, with emplacements set so that the attacking troops had nowhere to shelter from defensive fire. A further and more subtle change was to move from a passive model of defence to an active one. The lower walls were more vulnerable to being stormed, and the protection that the earth banking provided against direct fire failed if the attackers could occupy the slope on the outside of the ditch and mount an attacking cannon there. Therefore, the shape was designed to make maximum use of enfilade (or "flanking") fire against any attackers who should reach the base of any of the walls. Indentations in the base of each point on the star sheltered cannons. Those cannons would have a clear line of fire directly down the edge of the neighbouring points, while their point of the star was protected by fire from the base of those points.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Forts thus evolved complex shapes that allowed defensive batteries of cannons to command interlocking fields of fire. Forward batteries commanded slopes which defended walls deeper in the complex from direct fire. Defending cannons were not simply intended to deal with attempts to storm the walls, but to actively challenge attacking cannons and deny them approach close enough to the fort to engage in direct fire against the vulnerable walls. The key to the fort's defence moved to the outer edge of the ditch surrounding the fort, known as the covered way, or covert way. Defenders could move relatively safely in the cover of the ditch and could engage in active countermeasures to keep control of the glacis, the open slope that lay outside the ditch, by creating defensive earthworks to deny the enemy access to the glacis and thus to firing points that could bear directly on to the walls and by digging counter mines to intercept and disrupt attempts to mine the fort walls. Compared to medieval fortifications, forts became both lower and larger in area, providing defence in depth, with tiers of defences that an attacker needed to overcome in order to bring cannons to bear on the inner layers of defences. Firing emplacements for defending cannons were defended from bombardment by external fire, but open towards the inside of the fort, not only to diminish their usefulness to the attacker should they be overcome, but also to allow the large volumes of smoke that the defending cannons would generate to dissipate. Fortifications of this type continued to be effective while the attackers were armed only with cannons, where the majority of the damage inflicted was caused by momentum from the impact of solid shot. While only low explosives such as black powder were available, explosive shells were largely ineffective against such fortifications. The development of mortars, high explosives, and the consequent large increase in the destructive power of explosive shells. Plunging fire rendered the intricate geometry of such fortifications irrelevant. Warfare was to become more mobile. The costs involved in creating the fortifications were huge. Amsterdam's 22 bastions cost 11 million florins. Siena bankrupted itself to pay for the adaption of its defences. New defences were often improvised from earlier defenses. Medieval curtain walls were torn down, and a ditch was dug in front of them. The earth used from the excavation was piled behind the walls to create a solid structure. While purpose-built fortifications would often have a brick fascia because of the material's ability to absorb the shock of artillery fire, many improvised defenses cut costs by leaving this stage out and instead opted for more earth. Improvisation could also consist of lowering medieval round towers and infilling them with earth to strengthen the structures. It was also often necessary to widen and deepen the ditch outside the walls to create a more effective barrier to frontal assault and mining. Engineers from the 1520s were also building massive, gently sloping banks of earth called glacis in front of ditches so that the walls were almost totally hidden from horizontal artillery fire. The main benefit of the glacis was to deny enemy artillery the ability to fire point blank. The higher the angle of elevation, the lower the stopping power. The first key instance of trace italienne was at the Papal port of Civitavecchia, where the original walls were lowered and thickened because the stone tended to shatter under bombardment. The first major battle which truly showed the effectiveness of trace italienne was the defenses of Pisa in 1500 against a combined Florentine and French army. With the original medieval fortifications beginning to crumble to French cannon fire, the Pisans constructed an earthen rampart behind the threatened sector. It was discovered that the sloping earthen rampart could be defended against escalade and was also much more resistant to cannon fire than the curtain wall it had replaced. The second siege was that of Padua in 1509. A monk engineer named Fra Giocondo, trusted with the defenses of the Venetian city, cut down the city's medieval wall and surrounded the city in a broad ditch that could be swept by flanking fire from gun ports set low in projections extending into the ditch. Finding that their cannon fire made little impression on these low ramparts, the French and allied besiegers made several bloody and fruitless assaults and then withdrew. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Photographs of Star Forts |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

More on Types of Castle and History of Castles

Click on any of the following links to learn more about specific types of castle

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| :::: Link to us :::: Castle and Manor Houses Resources ::: © C&MH 2010-2014 ::: contact@castlesandmanorhouses.com ::: Advertising ::: |